Optimist at the Bench

Sophie Quick, Editor

Judge Hilary Charlesworth (1974) is the first Australian woman judge ever elected to the United Nation’s International Court of Justice. On a recent visit to her alma mater, Charlesworth reflected on her College days and life at the ‘World Court’.

Sunday 1 December 2024

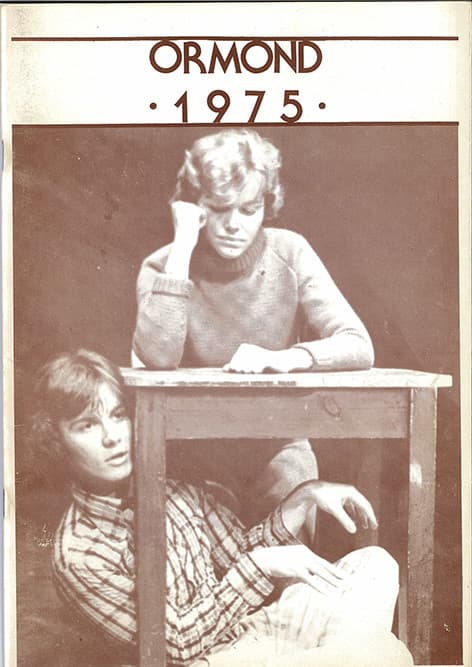

‘A series of accidents’ – that’s how Judge Hilary Charlesworth describes the extraordinary legal career that has taken her from Ormond College in Melbourne all the way to the bench of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in the Hague. But it’s clear that factors other than accident have played a role in Charlesworth’s trajectory. Her contemporaries from the mid-1970s remember a young woman with broad-ranging talents and a relentlessly enquiring mind.Charlesworth was reunited with some of those contemporaries in August at a special lunch in the Senior Common Room held in her honour. She met other Ormond alumni, staff and current students over lunch, and reflected on her time at College. ‘This was a wonderful place to be as a student,’ Charlesworth said. ‘Apart from being the place where I met my spouse and many other friends, it had a profound influence on me.’During her time at Ormond, Charlesworth threw herself into many aspects of College life – writing for The Chronicle, starring in theatre productions [alongside now federal Attorney General Mark Dreyfus (1974)] and meeting her future husband, Dr Charles Guest, then a medical student.It was not just her peers but also the former Master of Ormond College, Davis McCaughey, who made a strong impression on the young law student.

Still sometimes, when I find myself in a difficult situation, I ask myself: what would Davis McCaughey do? He was always calm in a crisis and had a way of listening to all points of view, never just imposing his solution to the problem.

Charlesworth said. ‘He was always calm in a crisis and had a way of listening to all points of view, never just imposing his solution to the problem.’Charlesworth’s interest in international law was sparked in her final year of study at Melbourne Law School. She went on to complete the Doctor of Juridical Science at Harvard Law School, to intern at the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and to pursue a career as an academic and jurist.The author of eleven books, she is celebrated as an original and highly innovative thinker, and has been recognised for her work to bring feminist theory into the study of international law. Charlesworth holds professorships at the University of Melbourne and the Australian National University.Today, of course, Charlesworth is based in the Hague, in the Netherlands, as a judge on the ICJ. Sometimes known as the ‘World Court’, it is the principal judicial organ of the United Nations. Charlesworth has served as a member of the ICJ since 2021 and was re-elected to the court in 2023.At the lunch in August, Charlesworth spoke about her work in the Hague. She is the first Australian woman to serve as a judge in the ICJ’s 78-year history. ‘I’m one of only four women out of 15 judges at the ICJ, so there’s still a long way to go.’During her time at the ICJ, Charlesworth has heard matters on some of the most pressing issues of our time – from state obligations regarding climate change to maritime boundary disputes and the conflict in the Occupied Palestinian Territory. In seeking solutions to incredibly complex problems, Charlesworth works with 14 judicial colleagues from vastly different legal systems, including the Chinese, Mexican, Romanian, Lebanese and Somalian legal traditions. ‘One of the most noticeable differences is that between colleagues from common law and civil law traditions,’ Charlesworth said.Charlesworth took questions from students and alumni on the evolution of the ICJ, the limitations of the United Nations and on the issue of compliance in international law. ‘The case load at the ICJ probably does reflect the paralysis of the Security Council,’ said Charlesworth. ‘But the court has sometimes shown the capacity to bring solutions to long-standing problems that have reached dead ends elsewhere. And, more broadly, people are always doing all sorts of other creative things to improve the legal machinery of the United Nations.’By way of example, Charlesworth reflected on the successful ‘veto initiative’ spearheaded by diplomats from Lichtenstein, which came into effect in 2022. States exercising their veto powers in the Security Council are now obliged to explain their actions at ensuing General Assembly debates.Charlesworth spoke, too, about an inspiring group of law students from Vanuatu. ‘They mobilised local and regional governments and they have campaigned to have the ICJ issue an advisory opinion on states’ obligations on climate change under international law.’While acknowledging the imperfections of the international law system, Charlesworth’s remarks carried a strong measure of optimism.‘I’m an optimist because even if the big wheels turn slowly, and have their frustrations, there are small wheels and new mechanisms that people – including young people – are bringing to bear on the system as a whole.’First Published in New & Old Magazine | Issue No. 104 December 2024