The Quest for the Lost Foundation Stone of Ormond College

Dr Glen Farrow OAM (1978)

In a captivating blend of history, architecture, and mystery, Dr Glen Farrow (1978) embarks on a personal quest to locate the elusive foundation stone of Ormond College—laid in 1879 but never found.

Thursday 9 October 2025

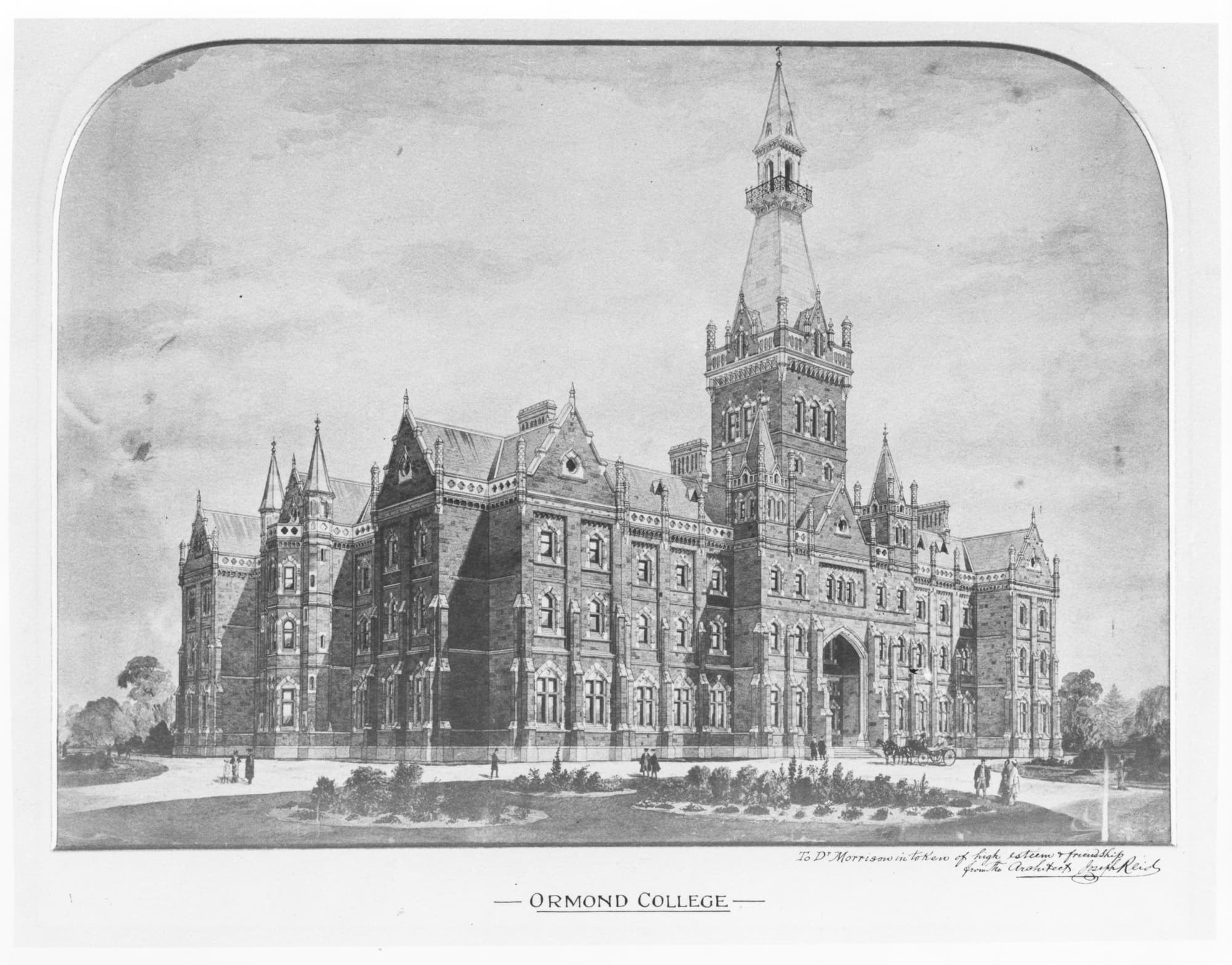

A few years ago, while clearing out my mother’s house after her move into aged care, I discovered a near pristine edition of the 1979 Ormond Chronicle sandwiched between two volumes of encyclopaedias. Expecting to read about my exploits in a kilt during second year Medicine I found a full-page advertisement for Peter Stuyvesant cigarettes and another for Naughtons Hotel when it was a proper pub. I remembered the sticky beer-soaked carpet smelling of cigarettes, the Ormond Oars over the front bar, and playing space invaders out the back. There was also a full-page “centerfold” of a recent male member of the Ormond College Council with a fig leaf appropriately placed.Amongst the articles was one written by Dr Rachel Faggetter, the Vice Master at the time. 1979 was the centenary year of the foundation of Ormond College on 14 November 1879. Despite searches in Ormond and University archives and external inspections, the foundation stone had not been found. In 1979 a small ceremony was held, and a memorial plaque was unveiled in the front foyer. I wondered if the stone had been found since, and surprisingly it had not. With 150 years not far away, I decided to set out on my own quest for the lost stone.Living in Sydney was no barrier. Since 1979 a thing called the Internet had been invented and many historical records digitised, so I began by looking on Trove for newspaper articles from the day. Several newspapers described a well organised ceremony when a “fine piece of formstone”, “admirably prepared” by Mr RS Ekins, the builder, was lowered into place. The Governor of Victoria, the Marquis of Normanby, laid some mortar and tapped the stone with a ceremonial trowel made for the occasion declaring the stone “well and truly laid” as was the custom. Francis Ormond was not in attendance, but many Presbyterian dignitaries were, including the Chairman of the Ormond Building Committee Dr Alexander Morrison, Headmaster of Scotch College.All the newspaper articles described a cavity either in, or below the stone, and a bottle containing committee papers of the time. None mentioned the location of the foundation stone, described as formstone. Formstone is stone that can be carved so it was not just another bluestone in the existing plinth. (on which many Melbourne buildings are built). The foundation stone in those days was the reference stone from which all other measurements were taken, so it was laid with precision and generally was a corner stone. It was an integral part of the building: not a memorial stone as we now see on the Victoria Wing.I also discovered an essay written in 1991 by Ormond resident Catherine Anderson as part of her Architecture degree. She had an interest in the original architect Joseph Reed of Reed and Barnes, and in the architecture of the College. Entitled “Scholastic Looking and Handsome: Joseph Reeds Ormond College, an architectural history 1881 - 1893” the essay covers much detail about the original buildings including their architectural plans. However, no plans showed a foundation stone, and its location remained a mystery.Consulting an old Professor of Architecture at the University of Melbourne I discovered that even though architectural plans were drawn up, builders made their own working drawings and were trusted to get on with the job. Prior to 1917 builders’ plans were not kept by the City of Melbourne. Builders notified the Building Surveyor that a building would be erected and paid a fee. On the 2nd of October 1879 Robert Ekins notified the Building Surveyor of the City of his intention to build and paid a fee of £3.10. On the 6th of October he indicated that building had commenced.If building commenced on 6th October, what was Mr Ekins doing until 14 November? Perhaps clearing the land and digging foundations. The foundations would be bluestone supporting the idea that the foundation stone was most likely not part of the foundations, but a cornerstone sitting atop the foundations.Searching for more documentation I traced the Ormond and Ekins family hoping a living descendant might have some information. Strangely Francis Ormond had burnt his papers before his last trip overseas. He adopted three children whose descendants are dispersed. Likewise, Robert Ekins, a prominent builder in Melbourne left all his belongings to his spinster daughter Elizabeth and the family has dispersed. I also looked for diaries of people present at the ceremony with little success. Dr Alexander Morrison, Chair of the Ormond College Council Building Sub-Committee and Headmaster of Scotch College, had kept a diary that only recently had been lost. I was told it was a very brief almost cursory document with no mention of the foundation stone.No mystery is truly mysterious without the involvement of the Freemasons. I looked at the ceremonial aspects of foundation stones which are based on the traditions of Freemasonry. Indeed, many of Melbourne’s wealthiest men were Freemasons including Francis Ormond. There is even a Francis Ormond Lodge in Melbourne to honour him. As already mentioned, builders used foundation/cornerstones as a working part of the building and referenced all measurements from it.If I were a Freemason, where would I place a foundation/corner stone? It turns out there are rules about this, just as there are many other arcane rules in

Freemasonry today. Foundation or corner stones are traditionally located at the northeast corner. The northeast corner receives the first sunlight of the day and symbolizes a new beginning, and the dawn of a project or endeavor. To add to the mystery, not all foundation stones were intended to be found.Sacrifices were placed under corner stones in Roman times. Today we place time capsules containing items such as newspapers, historical documents and coins. Placing the cornerstone correctly with an appropriate “sacrifice” was thought to bring the building good fortune.The College is orientated northeast to southwest. Several visual inspections over the years have not revealed a cornerstone. Could the stone be covered? The garden beds have not completely covered the bluestone plinth but there are other reasons the stone might be covered.The Victoria Wing was at first referred to as the Victoria Front, and its construction in 1887 covers one of the northeast aspects of the main building. If it covered the cornerstone this might explain the need for a memorial stone on the external walls of the Wing we see today. Indeed, at its unveiling Francis Ormond is said to have commented that the College needed a good memorial stone, and the Victoria Front was prestigious being named after Queen Victoria. The memorial stone also faces northeast.The essay by Catherine Anderson also references building techniques of the time. Grand buildings were common in Melbourne and included the Old Wilson Hall, and the Exhibition buildings, both designed by Joseph Reed. They have a bluestone plinth, iron girders and kauri pine timber frames, and brick walls covered in stone rubble. The external wall we see today is a layer of Barrabool Hill stone rubble intended to give a Scottish Gothic look. Was the original cornerstone covered by the layer of sandstone rubble?Is my theory about Freemasonry and the lost stone actually viable? A former Professor of Architecture thinks so, as well as other sources.If this foundation stone was not intended to be found it has succeeded in its mission. It might still be found by looking at the walls internally under the floor, which should be brick and may well have a cornerstone visible, but who wants to crawl under the College? Heritage surveyors can do this sort of work but should they? The stone has hidden so well for nearly 150 years perhaps it should be left alone. Maybe finding it will disturb the good luck of the College. Perhaps whoever finds it will die a mysterious death like Howard Carter.In my opinion we should continue the search. An inspection under the floor in the northeast corner; close to the library and the old Wyslaski Lawn would quickly prove or disprove my theory. Discovering its location in time for the sesquicentenary in 2029 would be quite something.If a search is mounted, I would like to be there, a modern-day Indiana Jones wearing my brown fedora, leather jacket and carrying a whip so that I can finally witness the discovery of the lost stone of Ormond College.

Freemasonry today. Foundation or corner stones are traditionally located at the northeast corner. The northeast corner receives the first sunlight of the day and symbolizes a new beginning, and the dawn of a project or endeavor. To add to the mystery, not all foundation stones were intended to be found.Sacrifices were placed under corner stones in Roman times. Today we place time capsules containing items such as newspapers, historical documents and coins. Placing the cornerstone correctly with an appropriate “sacrifice” was thought to bring the building good fortune.The College is orientated northeast to southwest. Several visual inspections over the years have not revealed a cornerstone. Could the stone be covered? The garden beds have not completely covered the bluestone plinth but there are other reasons the stone might be covered.The Victoria Wing was at first referred to as the Victoria Front, and its construction in 1887 covers one of the northeast aspects of the main building. If it covered the cornerstone this might explain the need for a memorial stone on the external walls of the Wing we see today. Indeed, at its unveiling Francis Ormond is said to have commented that the College needed a good memorial stone, and the Victoria Front was prestigious being named after Queen Victoria. The memorial stone also faces northeast.The essay by Catherine Anderson also references building techniques of the time. Grand buildings were common in Melbourne and included the Old Wilson Hall, and the Exhibition buildings, both designed by Joseph Reed. They have a bluestone plinth, iron girders and kauri pine timber frames, and brick walls covered in stone rubble. The external wall we see today is a layer of Barrabool Hill stone rubble intended to give a Scottish Gothic look. Was the original cornerstone covered by the layer of sandstone rubble?Is my theory about Freemasonry and the lost stone actually viable? A former Professor of Architecture thinks so, as well as other sources.If this foundation stone was not intended to be found it has succeeded in its mission. It might still be found by looking at the walls internally under the floor, which should be brick and may well have a cornerstone visible, but who wants to crawl under the College? Heritage surveyors can do this sort of work but should they? The stone has hidden so well for nearly 150 years perhaps it should be left alone. Maybe finding it will disturb the good luck of the College. Perhaps whoever finds it will die a mysterious death like Howard Carter.In my opinion we should continue the search. An inspection under the floor in the northeast corner; close to the library and the old Wyslaski Lawn would quickly prove or disprove my theory. Discovering its location in time for the sesquicentenary in 2029 would be quite something.If a search is mounted, I would like to be there, a modern-day Indiana Jones wearing my brown fedora, leather jacket and carrying a whip so that I can finally witness the discovery of the lost stone of Ormond College.